Whether you're looking to sell your company, or buy a competitor, it's important to know how to conduct an accurate business valuation.

My company is worth whatever someone is willing to pay for it. This is a bold statement made by business owners frequently, and it is code for simply saying, "I don't have the foggiest clue what my business is worth."

The reality is, what one person's willing to pay for something is not the value — it's an offered price. Hopefully, you won't settle an estate planning issue or sell your business based on this notion.

So, what is your company really worth? First off, you need to establish some background. Business valuations can be subjective, and generally accepted methods used to calculate fair market value can make Einstein's theories of relativity seem like simple math. Before you go further, you need to set the stage for the areas within your company that create value.

There are two separate assets within your company that have value: tangible and intangible assets.

Tangible assets are those assets that are physical and can be touched. They include vehicles, equipment, inventory, forklifts and computers, etc.

Intangible assets are those assets that are not physical and cannot be touched. These include the company name, reputation, customers and operating history, etc.

Anyone can figure out the fair market value of their contracting business' tangible assets. After all, it's based on the condition of each asset, with the lion's share being your fleet. Hardly anyone is prepared to sell their business based on only the tangible asset value, so that brings up the question of how to account for the value of the intangible assets.

Valuing Intangible Assets

By using your tangible and intangible assets, your company is able to provide services to your customers and, as a result, generate positive earnings. Positive earnings are an important point when discussing business valuations.

With the absence of positive earnings, the landscape of your business valuation changes significantly. Assuming your business hasn't been profitable for the last few years, it's better to engage the value of the tangible assets into something that might result in a return.

This alone suggests a business without positive earnings should be valued based only on the value of the tangible assets. This thought process makes sense, and many contractors have purchased a failing or defunct business based on the asset value alone.

Assume for a moment your business is profitable and has been for the past three years. Profitable means after you're paid and all discretionary and extraordinary expenses are taken into consideration. It's not enough to take income statements without considering adjustments.

Discretionary expenses are those expenses that reduce your operating earnings and may or may not be expenses that reoccur should a change of control happen. Extraordinary expenses are those expenses your business has incurred, but are highly likely never to reoccur.

An example of discretionary expenses may be excessive owner's compensation, while extraordinary expense might be costs associated with a disaster cleanup such as a hurricane, tornado, fire or flood.

Once your historical earnings are adjusted, only then does it become possible to understand the return on the assets your business requires. This return is what creates value and, ultimately, enables you to determine the fair market value for the combined tangible and intangible assets.

Now, if your business is 15 years old, you may wonder if you need to go back, analyze and consider all of the 15 years to determine what can be expected in earnings today. Not hardly.

It's not common for valuation analysts to look back past five years, and three years are more of the norm. Even then, the most recent 12 months are heavily weighed as the most significant. In a "what have you done for me lately world," this seems to make sense. In fact, many buyers of businesses look at only the most recent year.

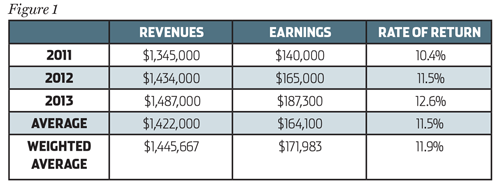

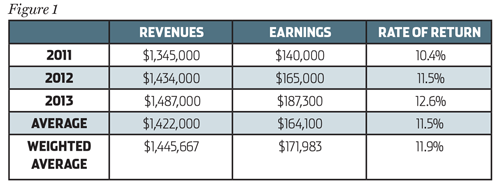

Three full years provides a solid run of results and helps to "smoke out" any wild swings in profitability (whether positive or negative). Commonly, an average of the last three years earnings are considered. Even better is a weighted average that places greater emphasis on the most recent period (Fig. 1).

Within this example, the company's weighted average revenues are $1,445,667 and earnings are $171,983 (11.9 percent). The weighted average is slightly higher than the three-year average due to the fact that a greater emphasis is placed on results from 2012 and 2013, and the company is showing some signs of economic prosperity.

An investor focuses on the economic return he or she will receive by investing capital into the acquisition. No historical earnings result in little to no returns. In this example (Fig. 1), there is a return, so an investor might conclude the earnings potential of the business ranges from $171,983 (three year weighted average) to $187,300 (most recent year's earnings).

Based on this assumption, all an investor has to do is buy this business and sit back and watch the returns flow. At approximately $175,000 a year, the investment is a sure bet — or is it?

Risks and Rewards

Whenever an investor takes risks into consideration, rewards must also be considered. An investor can place his or her money in numerous places, all of which have varying degrees of risks. The riskier the investment, the higher the expected return.

Investors commonly place capital into publicly traded stock. Large cap stocks are freely traded (liquid) and are relatively free from risks. Ask any financial planner and they'll agree that over a 10 year investment period, publicly traded stocks have consistently returned 10 percent.

With this being the case, no willing investor with a complete understanding of the facts would invest his or her capital into a privately held contracting business and accept a return anywhere close to 10 percent.

In fact, investors of riskier small cap stocks expect return much higher than 10 percent. These small cap stocks are publicly traded, but less proven then the Apples or the Exxon/Mobils of the world.

Small, privately traded businesses that can vaporize with the blink of the eye, or the turn of some horrific event, are fragile investments. In addition, your privately traded contracting business operates in an arena where there are no barriers to entry (highly competitive), relies on abilities of trained technicians and, by comparison to even the smallest publicly traded business, are tiny.

An investment into your company is highly risky and a reasonable investor will expect returns to exceed 20 percent.

Not all investments into contracting businesses should be based on a 20 percent return, as every contracting business has varying degrees of risk.

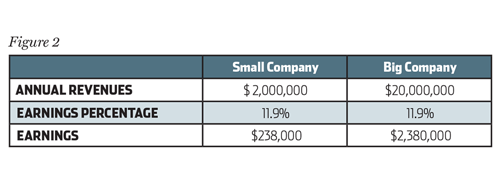

For example, compare a $2 million a year residential service and replacement contractor with an owner/operator who wears multiple hats, including that of the general manager, with a $20 million a year residential service and replacement contractor with a team of managers who divide up the responsibilities of the day-to-day operations.

With a larger base of revenues and a management team in place, the $20 million business is less risky and, therefore, an investment into this business should tolerate a lower return.

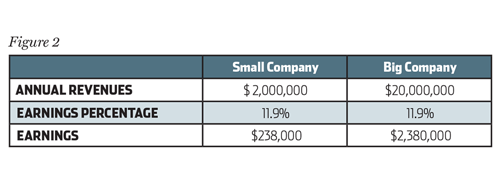

Assume each of these two businesses generates the same percentage of earnings (Fig. 2).

For the purpose of this example, assume the following:

- Investor pays 100 percent of acquisition at close

- Earnings will be constant in period of analysis

- Rate of return based on 10 years

Because Small Co. produces $2 million a year and relies heavily on the owner/operator; the risk of such an investment is significantly higher than an investment into Big Co. An investor might be able to tolerate lesser of a return for his or her investment into Big Co. as opposed to Small Co.

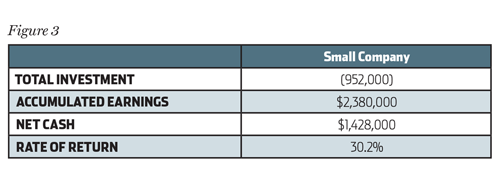

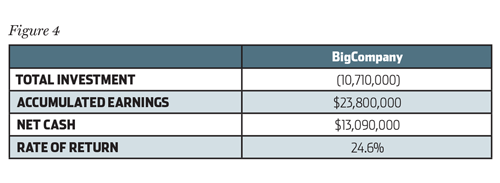

Let's assume an investor evaluates all the risks of both opportunities and settles on a return for each investment 30 percent for Small Co. and 25 percent for Big Co.

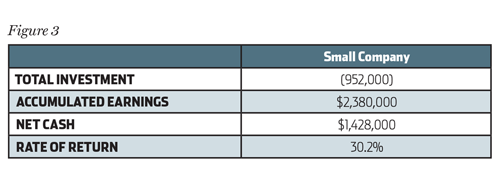

Based on those assumptions, he or she would be able to invest $952,000 today into Small Co. and over the next 10 years earn a rate of return of 30.2 percent, assuming 100 percent cash is paid on day one and the business performs exactly the same for the next 10 years. The accumulated totals are outlined in Fig. 3.

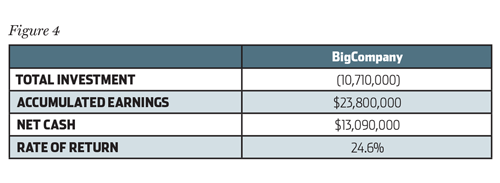

Following the same assumptions, and with an investment of $10,710,000 into Big Co., the rate of return would be 24.6 percent. The accumulated totals are outlined in Fig. 4.

Multiples

The multiple of earnings (or just multiple) has a direct correlation to the expected rate of return of an investment and not simply some arbitrary digit that sometimes gets tossed around as in "what multiples are they paying?"

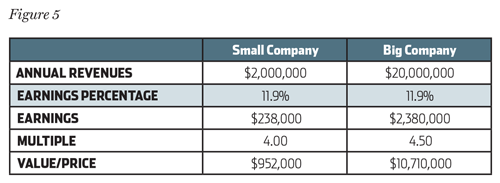

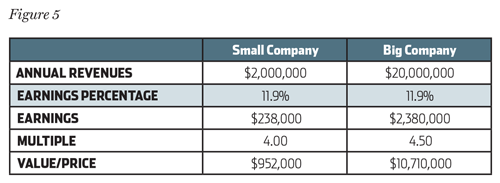

With the information from our above examples, we can see the multiple as outlined in Fig. 5.

Small Co. pays four times the earnings of $238,000, which results in a rate of return of 30.2 percent, whereas Big Co. pays a multiple of 4.5 times earnings, resulting in a rate of return of 20.2 percent.

If you've followed the examples all the way through, you now should have an understanding of why the multiples of earnings for contracting businesses range between 3 and 6.

Anything above a 6 multiple results in a return that is too low to justify an investment, as a 6 multiple loosely translates into a 17 percent return. At that point, an investor could take his or her cash and find safer places to invest.

It's critical to point out there's a range in multiples, and where the final multiple ends up for any one business is contingent upon the risk factors of the specific company. In our example, we determined Big Co. was less risky of an investment and, therefore, earned a higher multiple, which resulted in a lower expected rate of return for the investor.

Risk Factors

There are several key areas that can determine the risk factors of an HVACR contracting business. These include:

- Historical profitability net

- Historical profitability gross

- Size of business

- Age of business

- Momentum of business

- Work mix

- Customers

- Pricing

- Accounts receivable

- Service agreements

- Service fleet

- Employees

- Management

- Market

When taking the risks of each one of these areas into consideration, it's possible to determine the expected risk of the investment, and the multiple that should be applied to whatever earnings stream makes the most sense.

By applying this method, one can calculate the Enterprise Value of a business, which accounts for the value of both the tangible and intangible assets. It does not take into account assets such as cash, accounts receivable and inventory. In addition, the liabilities within the business must be considered as well.

The next time you hear a business owner declare his or her business is "worth whatever someone is willing to pay for it," you'll know that is not the case. In fact, his or her business is "worth whatever makes sense from an investor's viewpoint after determining what the adjusted earnings of the business are, and the expected return based upon the risk associated with those earnings."

Brandon Jacob is recognized industry-wide for his experience and knowledge in valuations, mergers, acquisitions and the ability to assist contractors in successful exit strategies. He's had numerous industry speaking engagements and multiple articles published within his area of expertise and has recently published "For What It's Worth," a contracting industry-specific book the explains how to value air conditioning and plumbing businesses. Brandon can be reached at Brandon@contractorscfo.com, or call 713-43-8311. For additional information, visit forwhatitsworthbook.com.

Brandon Jacob is recognized industry-wide for his experience and knowledge in valuations, mergers, acquisitions and the ability to assist contractors in successful exit strategies. He's had numerous industry speaking engagements and multiple articles published within his area of expertise and has recently published "For What It's Worth," a contracting industry-specific book the explains how to value air conditioning and plumbing businesses. Brandon can be reached at Brandon@contractorscfo.com, or call 713-43-8311. For additional information, visit forwhatitsworthbook.com.

Brandon Jacob is recognized industry-wide for his experience and knowledge in valuations, mergers, acquisitions and the ability to assist contractors in successful exit strategies. He's had numerous industry speaking engagements and multiple articles published within his area of expertise and has recently published "For What It's Worth," a contracting industry-specific book the explains how to value air conditioning and plumbing businesses. Brandon can be reached at

Brandon Jacob is recognized industry-wide for his experience and knowledge in valuations, mergers, acquisitions and the ability to assist contractors in successful exit strategies. He's had numerous industry speaking engagements and multiple articles published within his area of expertise and has recently published "For What It's Worth," a contracting industry-specific book the explains how to value air conditioning and plumbing businesses. Brandon can be reached at