However you decide to categorize expenses in your P&L, it's important to be consistent.

The definition of cost of goods sold (also called direct expenses) is any expense you have because you sold something.

In the strictest definition of the term, this means only materials, equipment, labor to install the job or maintain/fix the equipment, commissions, parking and tolls, permits, freight, warranty, maintenance agreement expense and subcontractor expense are included in cost of goods sold.

There are some gray areas. Some companies include labor burden and truck expenses. The reasoning for including labor burden is there is a burden associated with each hour of direct labor (FICA and Medicare expense, unemployment taxes, health insurance, worker's compensation, union dues, etc.) and these expenses would not be incurred if the employee didn't have an hour of labor.

With respect to truck costs, the thinking is if you didn't have to perform work at customers' homes or offices, you wouldn't have truck cost. Each employee has a truck and without a truck the employee can't do his or her job.

Some owners categorize labor burden and truck costs as overhead — and that's my personal preference (with the exception of travel expenses, such as tolls and parking at the job site). There is no right or wrong answer.

Put these expenses wherever you're comfortable, but be consistent. If you decide to put labor burden and truck costs in cost of goods sold, it has to be there every month. You cannot put it in cost of goods sold one month and overhead the next.

There are some labor expenses not related to production and should NOT be accounted for in cost of goods sold: vacation, holiday, sick days, meeting time, training time and other unapplied time employees spend doing non-revenue projects to get their hours in during slower times of the year.

If you put direct labor burden in cost of goods sold, then you have to split out the labor burden for labor expenses that are not in cost of goods sold. Some companies' computer systems make this easy. For others, it is better to include all labor burden in overhead expenses.

Shop material/ truck expense can be tricky. These are the little things that are hard to job cost: glue, wire nuts, caulk, duct tape, booties and screws, for example.

The best way to handle these expenses is to include their actual costs as a shop material expense when you purchase them. They're too small to go into inventory and here's why: I had a contractor who put these items in inventory and they never got taken out of inventory and added to job cost. As a result, his inventory at the end of the year was overstated by $15,000, which was the cost of all of the shop material purchases he made that year. This meant his profits were actually $15,000 lower than shown on his profit and loss statement.

Some contractors make the mistake of not including commission and the sales performance incentive fund (SPIF) payments in cost of goods sold. If the job was not sold, or the accessory/maintenance agreement not sold, then there would not be a payment to an employee. Commissions and SPIFs belong in cost of goods sold.

Be careful to put only the commission in cost of goods sold. If a salesperson has a salary plus commission, the salary goes in overhead since he or she receives it even when they don't sell anything. Only their commissions go into cost of goods sold.

If a salesperson has a draw against commission, the amount of the draw goes into overhead. There should be a maximum draw ($2,000 or $2,500, for example), which is your company's maximum exposure. Commissions earned are credited against the draw and expensed into cost of goods sold. The difference between the draw and commission is paid to the sales person.

If a one-year maintenance agreement is given with installations, the cost for that maintenance agreement is put in cost of goods sold. The offset is deferred income because it's a sale, but not earned revenue until the maintenance is performed (see Sales vs. Revenue, March 2015, pg. 15, for the description of sales and revenue).

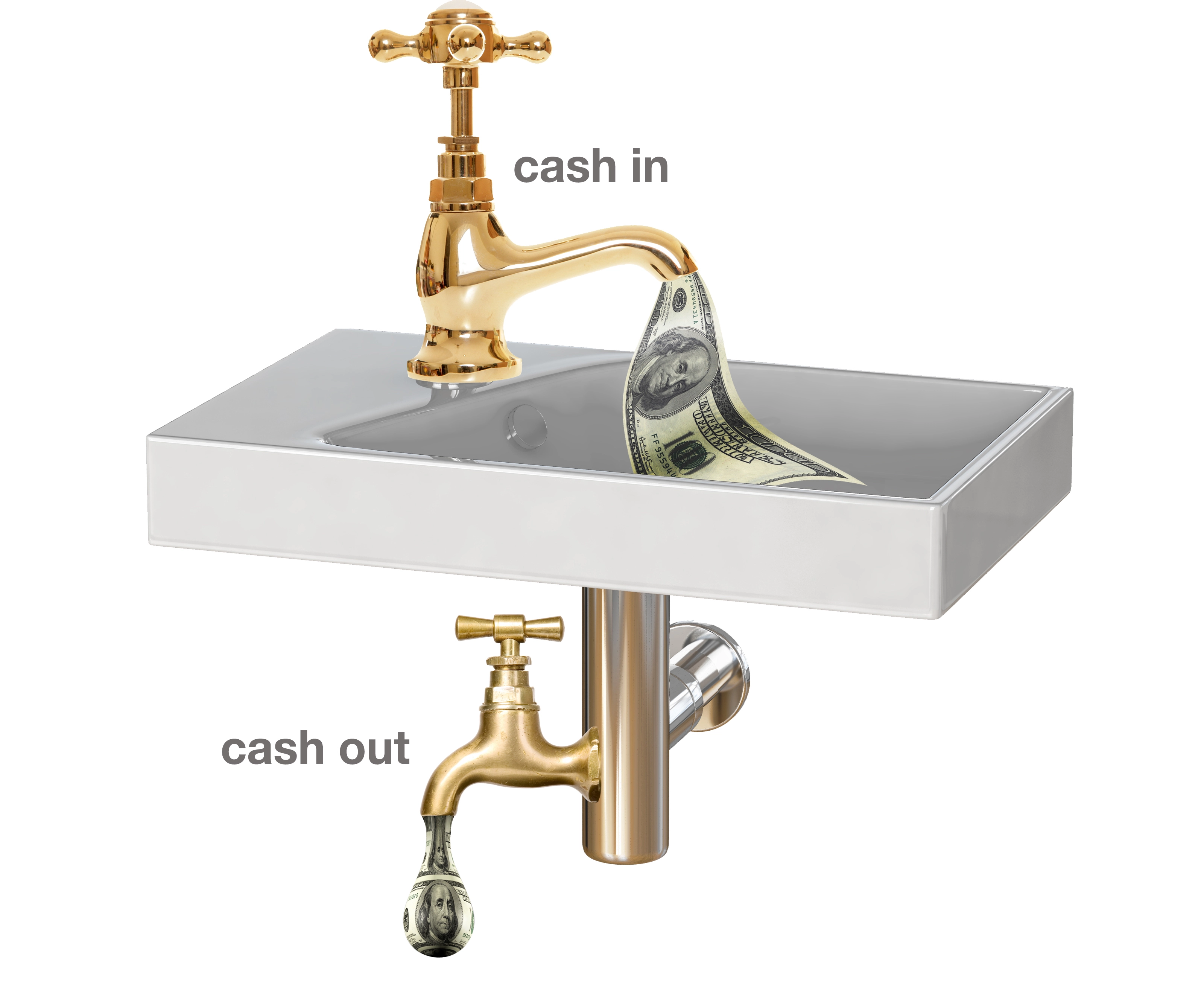

Sales minus cost of goods sold equals gross profit. Gross margin, which is gross profit divided by sales, should be consistent every month. Next month I'll show you where to look if your gross margins are not consistent.

Ruth King is president of HVAC Channel TV and holds a Class II (unrestricted) contractors license in Georgia. She has more than 25 years of experience in the HVACR industry, working with contractors, distributors and manufacturers to help grow their companies and make them profitable. Contact her at ruthking@hvacchannel.tv or call 770-729-0258.

Ruth King is president of HVAC Channel TV and holds a Class II (unrestricted) contractors license in Georgia. She has more than 25 years of experience in the HVACR industry, working with contractors, distributors and manufacturers to help grow their companies and make them profitable. Contact her at ruthking@hvacchannel.tv or call 770-729-0258.

Ruth King is president of HVAC Channel TV and holds a Class II (unrestricted) contractors license in Georgia. She has more than 25 years of experience in the HVACR industry, working with contractors, distributors and manufacturers to help grow their companies and make them profitable. Contact her at

Ruth King is president of HVAC Channel TV and holds a Class II (unrestricted) contractors license in Georgia. She has more than 25 years of experience in the HVACR industry, working with contractors, distributors and manufacturers to help grow their companies and make them profitable. Contact her at